Back to the Farms: Agriculture at the Heart of CBG’s Inflation Strategy, but Investment Falters

Central Bank Governor Buah Saidy © Askanwi

By Edward Francis Dalliah, Jr.

As inflation remains above target and dependence on imports deepens, The Gambia continues to struggle with the high cost of goods, particularly for staple commodities like rice, sugar, and flour. To curb this, the Governor of the Central Bank of The Gambia (CBG), Buah Saidy, has recommended more investment in domestic food production as a key route to price stability. Nevertheless, persistent budget execution gaps, issues of transparency, and longstanding weaknesses in the agricultural sector raise doubts about whether this strategy can achieve the desired results.

On 4th December 2025, during a Monetary Policy Press Conference, Governor Saidy, while answering the question of our reporter, said the Bank’s push toward its 5% medium-term inflation target depends largely on boosting local food production, an approach he stressed goes beyond the Central Bank’s mandate.

The governor said CBG is “trying to ensure that we achieve this 5% medium-term target through increased domestic food production, and that is not the responsibility of the central bank alone, but the entire government machinery.” Moreover, he also urged citizens to return to agriculture, warning that heavy reliance on imports continues to undermine economic stability. “But every Gambian must be willing to go back to the farms. We have to increase our food production. We cannot depend on imports,” he told our reporter.

The Central Bank at the start of 2025 had projected that inflation would fall to its 5% medium-term target by the end of the year, but as of October, inflation has remained elevated at 7%, two percentage points above the target. Despite this, Governor Saidy remained optimistic, stating that by the “first quarter of 2026, we should be able to reach the medium-term target,” adding that this would be achieved “through increased domestic food production.”

However, economists argue that the governor’s position reflects a structural reality, as inflation in The Gambia is largely imported. Food items such as rice, flour, sugar, and cooking oil, staples consumed daily across households, account for a significant share of the country’s import bill. As a result, global price increases, shipping costs, and exchange-rate depreciation are quickly passed on to local markets.

Economist and agropreneur Dr Ousman Gajigo told Askanwi that “the Gambia imports 90% of the rice we consume,” and our review of the Gambia Bureau of Statistics (GBoS) International Merchandise Trade Statistics (IMTS) revealed that in 2024, rice topped the “Imports of Selected Products for 2024” section, amounting to D4.8 billion.

Top three imported products to The Gambia in 2024 © Askanwi after GBOS

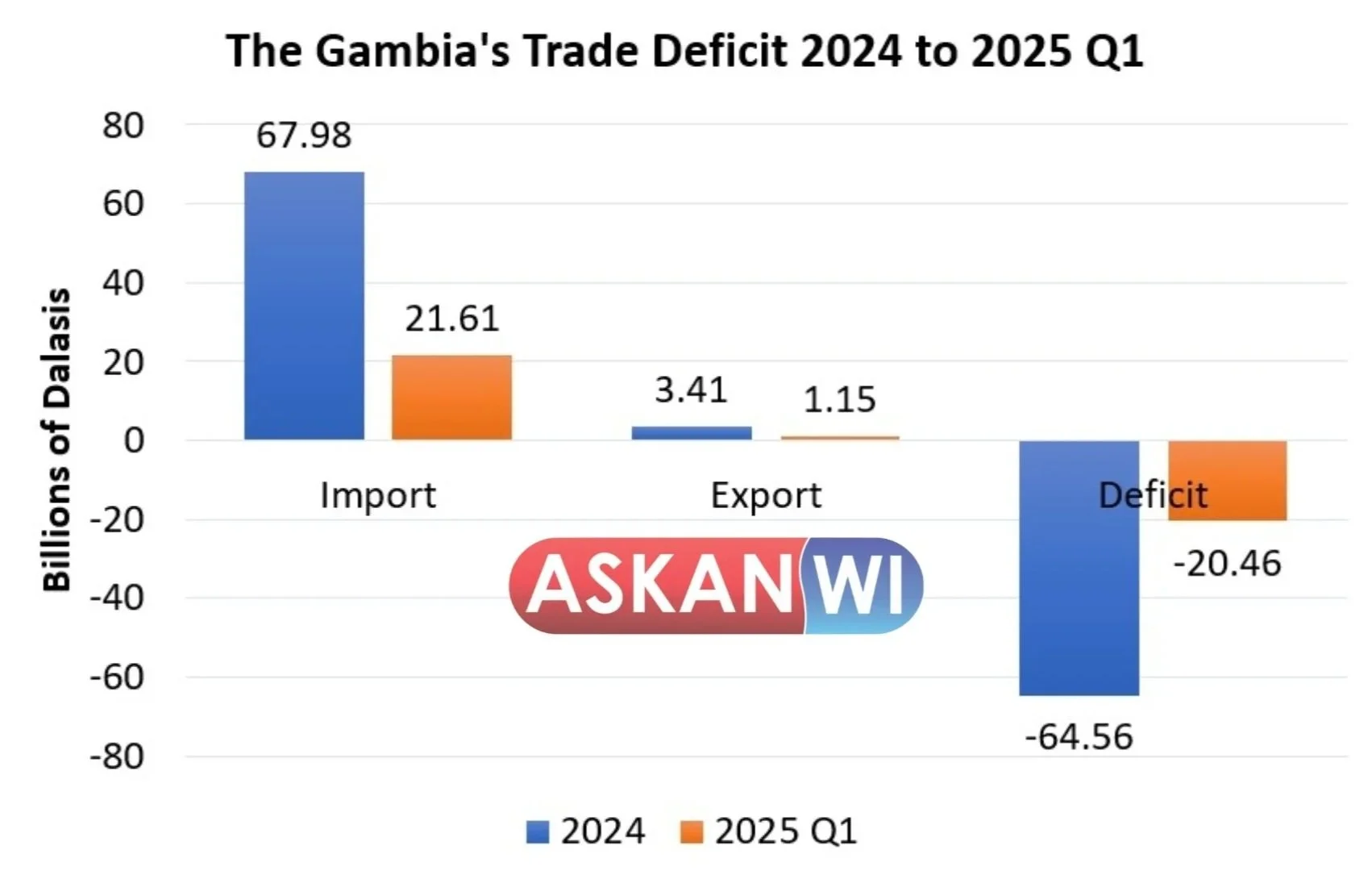

Additionally, based on the document, Gambia recorded a record trade deficit of D64.6 billion in 2024, driven by rising imports and a narrow, undiversified export base.

The trend continued in early 2025 as imports surged by 37%, compared to the first quarter of 2024. Imports increased from D15.8 billion in the first quarter of 2024 to D21.6 billion in the first quarter of 2025. This highlights that the country’s import dependence is increasing.

Exports, meanwhile, declined by 3%, falling from D1.18 billion to D1.15 billion over the same period. This highlights that the country is going backwards with regard to boosting exports. Most notably, the GBOS data shows a decline in exports to other African countries in the region, including Senegal and the rest of West Africa.

This resulted in a trade deficit of D20.45 billion in just three months, reinforcing concerns about the country’s growing reliance on foreign goods and the challenges this poses for inflation control.

Compared to the whole of 2024, when the record trade deficit of D64.6 billion was recorded, the country is on track to record a deficit exceeding D80 billion for 2025.

If imports continue to surge and exports continue to falter, the country is on track to break last year’s trade deficit record by the end of 2025.

The Gambia’s Trade Deficit 2024 vs 2025 Q1 © Askanwi after GBOS

‘Eat what you grow and grow what you eat’ has been replicated throughout the years, from the first administration of President Jawara, through former President Jammeh, and now it’s being echoed in the current administration of President Adama Barrow.

President Barrow’s second National Development Plan, dubbed “YIRIWAA” (2023–2027), marks agriculture as a priority sector and positions it as central to food security, economic transformation, and macroeconomic stability.

In the government’s 2024 Yiriwaa Progress Report, the government noted that agriculture’s “growth declined over the year under review, with 20.6 percent compared to 23.4 percent in 2023. Moreover, the sector’s growth rate decreases to -1.1 percent, down from 3.7 percent in 2023.”

The document noted that the sector “is primarily rain-fed, and seasonal changes impact production and overall output. [Likewise,] small-scale farmers dominate the sector, growing crops mainly for household consumption rather than for large-scale production.”

Dr Gajigo attributed the sector's low productivity “to inadequate spending on irrigation and essential inputs.” He argued that “the reason for these outcomes is that the government has not made the required investments in irrigation infrastructure and essential inputs” and cautioned that “the past trends in low production and productivity should be expected to continue unless policy changes are made.”

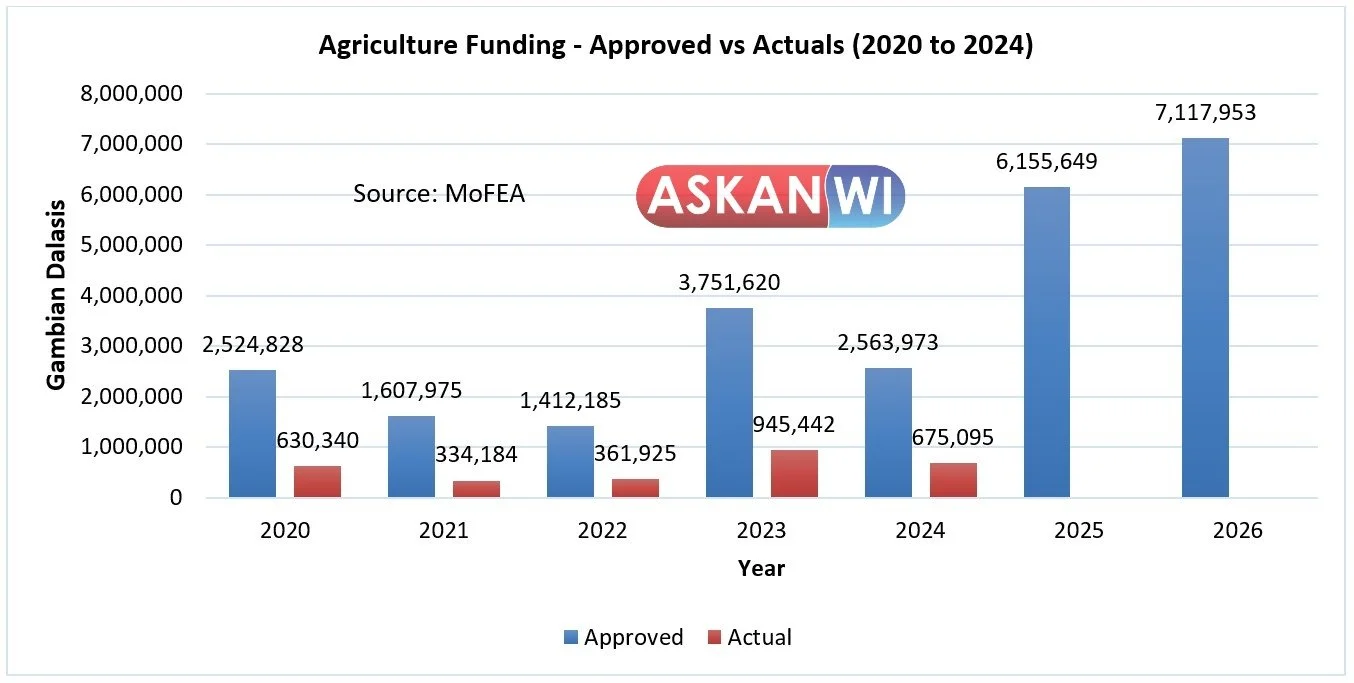

One of the main policy documents, which is the national budget, shows increases in agricultural allocations, including in the 2026 Budget. However, the actuals reported remain insufficient to drive the scale of productivity required to meaningfully reduce food imports.

The co-founder and head of the Center for Budget and Macroeconomic Transparency (CBMT), Mr Lamin Dibba, told Askanwi that the gap between approved and actual spending raises questions about the government's commitment to the agricultural sector.

He pointed out that “the government-approved allocations to the sector are quite significant and huge, and these allocations, if you look at them, align with the sector's strategic importance to the economy. However, the actuals that are reported in the budget are quite low and reflect the other side of the scenario: that the sector is not regarded as important when actual allocations are being done.”

Agriculture Funding - Approved vs Actuals in Thousands of Dalasis © Askanwi after MoFEA

The above chart shows a clear picture of what Mr Dibba is pointing at.

Our review of both approved allocations and actuals reported in a series of budgets from 2019 to 2026 revealed that the government normally allocates a significant amount to the sector; however, the actuals reported always fall short of the sector's priority.

Our analysis of budget execution from 2020 to 2024 shows that although D11.8 billion was approved for agriculture from all funding sources, including the General Local Fund (GLF), loans, and grants, only D2.9 billion was reported as actual expenditure.

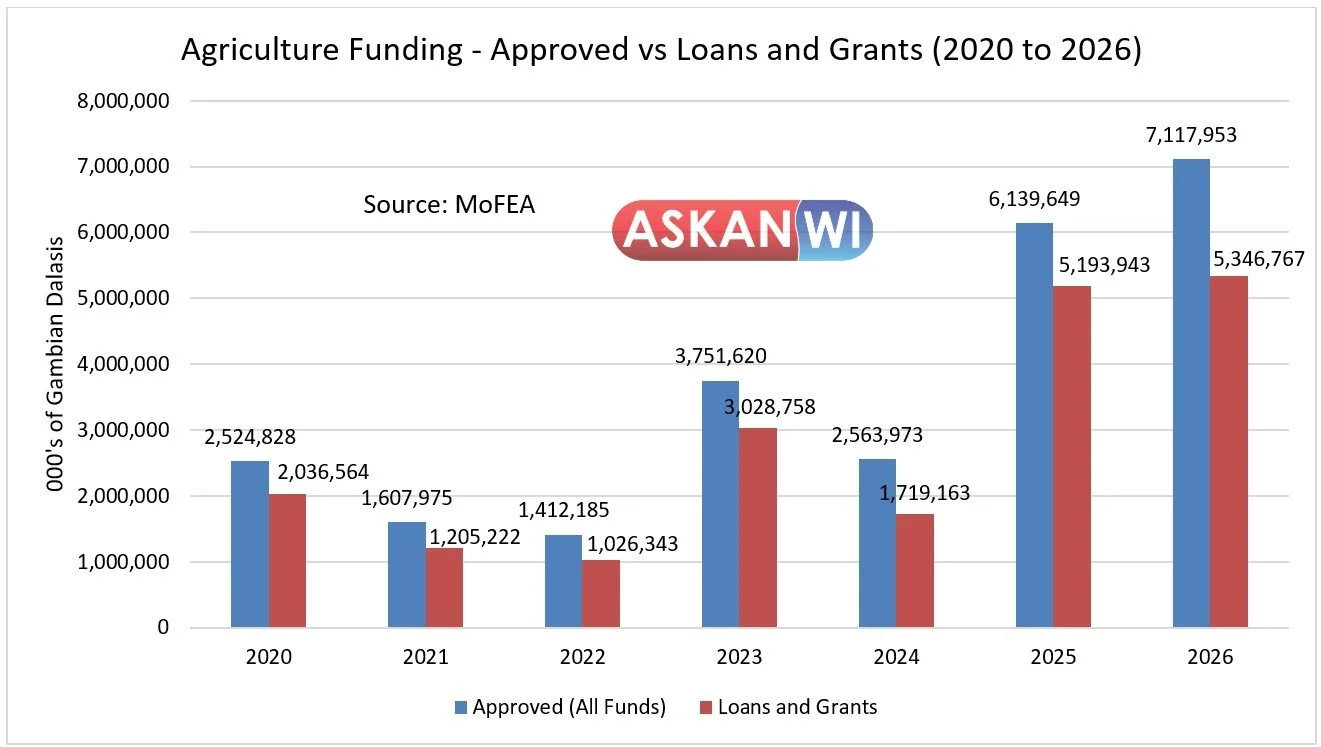

Further investigation by our reporter shows that the sector is heavily dependent on loans and project grants, which most of the time amount to about 70% to 80% of all fund allocations.

Agriculture Funding showing Approved vs Loans and Grants in thousands of Dalasis © Askanwi after MoFEA

The above chart shows a clear picture of how the government heavily depends on loans and grants.

This dependency was confirmed by the Finance Minister, Hon. Seedy Keita, during an interview on Coffee Time with Peter Gomez on 11th March 2025. The Minister, while responding to concerns raised by the United Democratic Party regarding the government’s GLF allocation on agriculture in the 2025 budget, noted, “Most of the support in agriculture are grant funds, so it is just to implement, and this support are from our development partners. That is why we take that on board and [are] fully cognisant of that fact. We support the agricultural sector from our limited government resources.”

He added that the “sector has more than D5 billion support in [the] form of grants from partners, [like] IFAD, World Bank, ADB, IDB, OPEC.”

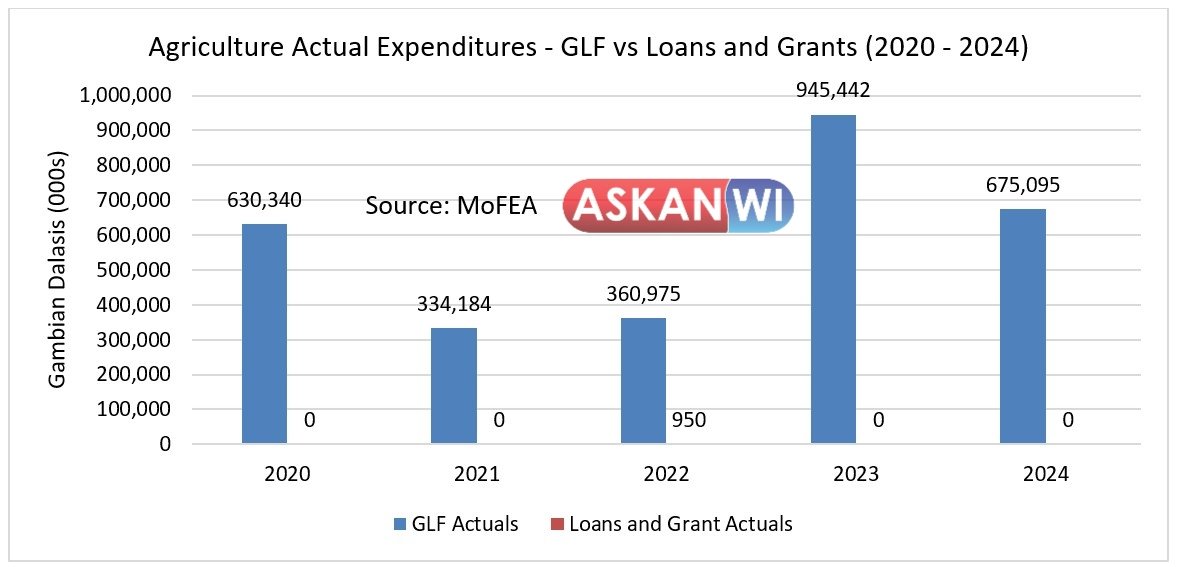

However, our reporter has discovered that, in terms of actual reported figures for these grants and loans, only in 2022 did the Ministry of Agriculture report receiving funds from this allocation.

While GLF spending broadly matched approvals, with D2.8 billion approved and D2.9 billion recorded, externally financed projects underperformed sharply. The approved loans and grants of D9 billion translated into just D950 thousand in reported actuals.

In all other years from 2020 to 2024, based on the budget figures, no funds were received from partners, be they loans or grants. This raises a serious question, given that the sector relies on this allocation.

Commenting on the issue, Mr Dibba told our reporter, “There is massive under-reporting of the money received by the agriculture ministry when you look at the budget. So, you cannot tell if, in fact, the deviation between the approved and the actual amount, as far as the agricultural sector is concerned, is correct.” This now raises serious questions about transparency and accountability.

Agriculture GLF vs Loans and Grants Actual Expenditure © Askanwi after MoFEA

Askanwi questioned both experts on whether agriculture can help tame inflation, and in response, they agreed that sustained investment in agriculture could play a decisive role in reducing inflationary pressures.

Dr Gajigo explained that the country’s “inflation is determined mainly by the cost of imported items. Some of our biggest import items are agricultural commodities such as rice. If the country were to invest in agricultural production and we produced rice rather than importing it, rising import prices would not be transmitted to us and increase our inflation.”

He added that reducing imports would also ease pressure on the dalasi. “The reduction in imports would reduce the trade deficit, which would also reduce the depreciation pressure on our currency, further curtailing price increases,” he told our reporter.

Mr Dibba similarly pointed out that “effective budgetary spending, the mechanisation of the sector and access to finances to farmers at a low or no interest rate” can provide a pathway to reducing import dependence and higher domestic output, which “will reduce external stocks because we will not depend so severely on agricultural products.”

As the Central Bank pushes toward its 5% inflation target, the debate has shifted from rhetoric to results. The challenge is no longer whether Gambians should return to farming, but whether government policies, budget execution, and institutional support can make agriculture productive, profitable, and sustainable.

Looking ahead, approved agricultural funding for 2025 and 2026 rises to D13.2 billion, exceeding the combined approvals of the previous four years. Of this, D2.7 billion is projected from the GLF and D10.5 billion from loans and grants, once again highlighting the sector’s heavy reliance on external financing and raising concerns over whether these allocations will materialise into meaningful investment.

Until those gaps are addressed, experts warn that domestic food production may struggle to play the stabilising role the Central Bank is counting on, leaving inflation stubbornly above target and households exposed to rising prices.